If War Makes States, What Has Karabakh Made of Azerbaijan and Armenia? – Itır Bağdadi

- E-ISSN: 2718-0549

-

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15402.85443

Abstract

The recent clashes between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Karabakh have led to a polarization of experts, media and public opinion around the world. Extremist rhetoric on both sides clouds the underlying reasons for the end of the ceasefire that has largely been in effect (albeit with a few setbacks over the years) since 1994, cementing a status quo unacceptable for Azerbaijan. Since the ceasefire, Azerbaijan has been committed to regaining its lost territories and has modernized its military, alliances and bureaucratic structures to achieve this aim. Armenia, on the other hand, has largely depended on international institutions and Russia to keep the status quo and has largely neglected alternative solutions that might bring about a change in the borders of the territory under its control. International institutions also benefitted from the frozen status of the conflict and did not necessarily enforce any of the peace deals that they had mediated. This article explores how the Karabakh War has impacted both Azerbaijan and Armenia since the ceasefire that created a 26-year status quo in the region and calls attention to the need to implement a comprehensive plan to bring peace to Karabakh.

Keywords: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Karabakh War, state-making, war-making

Introduction

“War makes states,” Charles Tilly famously claimed when analyzing how coercive exploitation played a part in state-making.[i] Although Tilly did not specifically address post-Soviet states in his seminal work published some years before the collapse of the USSR, it is obvious that the presence of war had a significant impact on the states that emerged out of the rubble of the USSR. In the case of the South Caucasus, Georgia faced wars in several breakaway territories within its borders, and Azerbaijan and Armenia fought over Nagorno-Karabakh, situated and internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan with a predominantly Armenian population. The trajectory of the war, made and remade all these states while they faced the triple transition of democratization, marketization and state/nation-building.[ii]

When attempting to analyze the current developments in the South Caucasus, more specifically the end of the ceasefire in late September of this year between Azerbaijan and Armenia that had been in effect since 1994 (albeit with a few setbacks over the years [iii]), it is important to remember that the presence of war has been an element in the state and nation-building of these countries. It has guided the rhetoric, narrative and practices of the triple transition these states have faced since their independence from the Soviet Union in 1991.

The end of the Karabakh status quo

Perhaps one way to analyze the recent conflict is by looking at the socio-economic and demographic developments of the region to see how the past fuels the war. To begin with, it should be noted that the loss of life – any life – whichever side it is on is a sad and heartbreaking thing. This includes the lives of not only civilians (who should be guarded under international humanitarian laws) but also military personnel – many of whom are conscripted young men who may be on the battlefield unwillingly and under the threat of greater violence from their home countries.

As we are all bombarded with information about the gains of one side and the losses of another side, and the pressure from outside patrons with biased positions, it is quite clear that this war is being fought not only on the battlefields of Karabakh but also in the media.[iv] The post-truth era is full of misleading information, but the Karabakh conflict has brought it to new heights. The presence of extremists on both sides has silenced those trying to find the middle ground and words like ethnic cleansing and genocide are thrown around by each side every day.[v] Social media, with its own algorithms also creates its own extremists since, if you are prone to one point of view, you are constantly bombarded with posts that portray those perspectives. It is possible that in this war, there may be two victors – one on the battlefield and one in international public opinion. Thus, a first step towards toning down the war will have to start with a media plan that includes unbiased inclusive language of both sides.

One issue that has come to the forefront in this war, though it has been also visible in other conflicts, is how the Western press treats those that it deems non-Western “outsiders”. As one browses through the Western press, it may seem that they are immune to the pain and suffering of non-Western and especially non-Christian societies. This especially rings true when the perpetrator may be a group that was previously victimized themselves in history. This lack of concern for “the other” then creates a vicious cycle and lack of trust in Western mediators, institutions and leaders. Objectivity, it seems, has never existed in this conflict for states trying to find solutions. Turkey and Russia are not – and cannot be – impartial and objective, nor are they expected to be, although the expectation of staying away from physical fighting on another state’s behalf is rightfully awaited. Yet, the other states should also break free of their biases – which they have not been able to do so until this point – if they are wish to take part in mediation between the warring states.

Plain and simple; Armenians won the last war that resulted in the ceasefire of 1994. This traumatic event has had a significant impact on the state-building of Azerbaijan, as the top leadership was ousted in tandem with the military losses in Karabakh. In fairness to the Azerbaijanis however, we should acknowledge that they had no real army, there was a vacuum at the very top with several different groups trying to control the state, their soldiers had no real background in the Soviet army that gave them training as most Muslim citizens of the USSR were placed in construction battalions and non-fighting roles in the Soviet military, and they had not yet started receiving the wealth of their oil.

The Armenians had the upper hand as the international context was in their corner, Russia was very supportive of Armenian claims and the Armenian diaspora poured money and fighters into the region. Moreover, many military personnel that were unemployed because of the collapse of the Russian economy served as mercenaries on the side of Armenia as well. This is why I find references to any mercenaries in the current war as being some sort of a violation of international norms interesting since the first war had so many mercenaries that fought on the Armenian side.

The ceasefire resulted in a frozen conflict where the two sides were expected to commit to making concessions, which – if you look at the latest outcome resulting in the Madrid Principles – was very accommodating towards the victor of the war.[vi] The Karabakh Armenians would get a link with Armenia proper with the Lachin corridor, international peacekeepers would provide security guarantees and the final legal status of Nagorno-Karabakh would be determined through a legally binding expression of will with Karabakh having self-governance. All sides agreed to these terms, yet none of the territories were returned and a status quo ensued for many years. No frozen conflict in reality remains frozen and it seems obvious now that the Armenians did themselves a disservice by not locking in their gains when they had the upper hand. All frozen wars are thawing wars and Armenia is learning this the hard way.

What Has Changed?

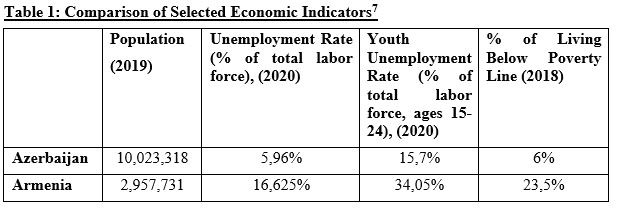

What has changed in the 26 years since the ceasefire? First of all, there is no longer an internal struggle for power in Azerbaijan since it has been ruled dynastically by first Heydar Aliyev (1993-2003) and then his son İlham Aliyev (since 2003), who is currently the President. Secondly, the oil-wealth has increased the influence that Azerbaijan wields on the international stage and has also given it a strategic importance among many Western states. Thirdly, while Azerbaijan has flourished economically, Armenia has gone in the opposite direction (see Table 1).

We can sidetrack and talk about the lack of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan or how the income has not been equally distributed – as many proponents of Armenia are doing – but that does not change the fact that the public support for the latest war to “reclaim Azerbaijan’s territory” is extremely high in Azerbaijan. Just scroll through the internet feeds of opposition voices that have had to leave Azerbaijan – not much criticism even among those that are extremely opposed to Aliyev himself.

Armenia, on the other hand, has had to deal with economic downturn, brain drain of its younger population, high unemployment, a negative migration rate, loss of its energy supplies from Azerbaijan and loss of trade with both Azerbaijan and Turkey which are blockading it economically.[vii] The active Armenian diaspora cannot make up for this economic deficit and while they fuel the war sitting at their keyboards in Los Angeles, New York, Paris and elsewhere, they do not and cannot support every day Armenians who are left behind to live in post-war Armenia. Approximately one in four people in Armenia lives below the poverty line.[viii] It has been said that the diaspora tries to resurrect the dead while forgetting about the living. The upper hand that Armenia held in 1994 has diminished as it no longer has the wealth, population or international support it once did. Many Armenian political leaders have exploited the nationalism around Karabakh to keep themselves in power. One expert suggested the title “How Nikol Pashinian lost Karabakh” as a headline worth considering.[ix] Just looking at the demographics of both of these countries makes the current developments a no-brainer.

Instead of focusing on the real socio-economic and demographic reasons for poor performance of its Armed forces so far, the current rhetoric in Armenia about Armenian losses has centered around their victimization throughout history, especially at the hands of the Turks. While the victimization is also embedded in Armenian national and cultural identity, victims of the past can also be victimizers in later years, and to refer to past traumas not related to current events only creates a narrative and deadly cycle of hate and mistrust. Both sides in this war are guilty of crimes against the other group. As traumatic as the events of 1915 were, Karabakh is not Eastern Anatolia and for centuries during the Russian empire and the USSR, Armenians and Azerbaijani Turks co-mingled and settled across this territory. Karabakh is diverse and its history does not belong to only one group, nor does the history of violence. Look back on past events and you will see Azeris killed in Hodjali and Kelbajar, and elsewhere, and you will see Armenians killed in Sumgait and Baku. Many of the so-called experts one reads these days only underline the killings of one group and completely omit the lives of the others. How can we expect impartiality from those that use a biased framework to begin with?

Clashing Claims over Karabakh

If an identity based on victimization is one part of the story, ancestral claims to Karabakh are another. As moving as this may be, biblical claims to land are not a legitimate legal basis to change state borders that exist under international law. There are several UN Security Council Resolutions that clearly outline the status of Karabakh and under which country’s borders it lies. We cannot pick and choose which part of international law we want to respect – that would set a very dangerous precedent for future international conflicts.

While it is true that the Karabakh Armenians of the USSR petitioned to be included in Armenia, those petitioning did not include the Azeri citizens living in the territory, so the process was exclusionary to begin with. In addition to this, nowhere in any of the USSR borders were the additional 7 regions – occupied by Armenian forces since the early 1990s outside the Nagorno-Karabakh- included as part of Karabakh. Claiming them as part of a newly imagined “historical homeland” with a different name does not create a legal basis for international recognition. The USSR fell apart and 15 new states came out of its rubble, and none of the disputed territories or sub-regions in any of the other states have been recognized internationally.

Moreover, causing the Azerbaijani population to flee and then claiming their land (especially in places like Shusha where a majority of the population were Azerbaijanis) presents a violation of the rights of those residents / citizens. Many of the Azerbaijanis who have been internally displaced are still alive holding on to the keys of the homes they were forced to abandon. These memories obviously create resentment that has fueled the current war.

In addition to ousting several presidents from office and leading to the consolidation of the House of Aliyev, the defeat in Karabakh in the early 1990s has also had a more grassroots impact. Due to the conflict, Azerbaijan has one of the highest numbers of internally displaced persons (IDP’s) in the world.[x] None of these people had any say in the current government of Karabakh, nor are they allowed to go home, making it impossible to call an area cleansed of one ethnic group the democracy it claims to be. These IDPs are not only a financial burden on the state of Azerbaijan, they are also voting citizens that demand to return to their lands. The presence of these IDPs also keeps the frozen conflict alive every day in society and politics. Aliyev may not be a democrat, he may be oppressive, but one cannot argue against the widespread public support he has on the issue of Karabakh.

International Scene

The bulk of recent Armenian ire is aimed at Turkey, seen as the “big bad wolf” who changed the status quo of the 1990s and encouraged as well as empowered Azerbaijan to regain territories. Without a doubt, Turkey supports Azerbaijan, ideologically and with military insight and weapons it sells. But the extent of that support is grossly overexaggerated by the Armenian diaspora. Turkey supported Azerbaijan during the first war as well, though it was not in a position internationally to do so at the level it is doing today and it did yet not produce the weapons that it has sold to Azerbaijan recently.

Listening to many webinars, interviews and statements of experts on this conflict, one finds that most Armenian “experts” are erroneously claiming that Turkish support on the ground has shifted the balance of power. This argument only serves to undermine Azerbaijan’s own military personnel. It is no secret that Azerbaijan has been preparing for this war for a very long time. They have been training their military, and buying expensive weapons not only from Turkey but also from Israel and Russia.[xi] They certainly have the oil wealth to do so. This is not a Turkish military victory, the victories are all Azeri, but with the support of Turkish backing on the international political front which has had an impact on Russian and Iranian involvement in the conflict. Also, we should not underestimate the changes in the international climate. Certainly, Russia is not as supportive of Armenia as it was in the early 1990s, as well as the Western countries where the Armenian Diaspora is still very active.

This drive to paint Azerbaijan as “perpetual military losers with no real military prowess” is keeping many of the so-called experts from seeing the bigger picture. This is as much a loss of vision in Armenia as it is a victory for Azerbaijan. This conflict was bound to happen, so the real question is why were the Azeris were so prepared and the Armenians so unprepared? Some experts who travelled to Armenia in the past state that they had expressed to the Armenian leadership the need to compromise but that they were not heeded, with one military commander stating that Armenia would even take Baku if the Azeris tried to retake Karabakh.[xii] There is a need to detox the state of these types of nationalists that have kept Armenia from moving forward in peace negotiations.

Almost 30 years have passed since the dissolution of the USSR, 26 years since the ceasefire between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Many mediators, institutions and negotiators have tried their hand at solving this conflict. Yet not one territory was returned, not one legal change was made. Suffice it to say that this war and the frozen conflict of the past 26 years is also a failure of the international community and its institutions. As Thomas De Waal, a leading expert in the field, recently stated on his Twitter feed that the CSTO, EU’s Eastern Partnership and the OSCE are all going to have to take a hard look at themselves and some of these institutions may not survive after the conflict.[xiii] For years many experts made tons of money by providing analyses which led to the current situation we are in. It is almost as if the international community wanted to keep this frozen conflict as long as it could and made no real push to resolve it and certainly did not enforce any of the principles that were mediated. As a peacemaker in the region, Arpi Bekaryan noted that they “did not speak and only whispered” and it seems clear that those receiving grants for peace-building actually acted against it because peace requires a comprehensive plan.[xiv]

While the focus so far has been on Azerbaijan’s changing military capabilities and its successes on the battlefield, not enough credit has been given to its diplomatic corps. For many years I have worked with and watched many young, talented Azerbaijanis learn the intricacies of international organizations, extend their international network, and master different languages -aside from their native Azerbaijani Turkish, they are native in Russian and well versed in English and French as well. This is one of the reasons why the international community is not reacting to Azerbaijan the way it once did. Contrary to popular thinking, not all of the oil money went to weapons and corruption, some of the money was invested in bringing the best scholars and experts to Baku to train up and coming individuals in public diplomacy.[xv] It is certainly paying off now.

Conclusion

So where do we go from here? With grassroot support and massive investments into military equipment and weapons, it seems that Azerbaijan is gaining significant territory on the ground and it is looking more and more likely that the terms of the previous ceasefire may no longer hold. International negotiations over the future of Nagorno-Karabakh will need concessions from Armenia that were not on the table in 1994. In keeping with Tilly’s work, the impact of this loss will obviously have an impact on domestic Armenian politics. Unlike more pessimistic commentators however, I believe it is possible for Azerbaijanis and Armenians to live together in peace. But for that to happen, any future peace deal needs to create an economic bond for the Karabakh Armenians with Azerbaijan. It should also be noted that, even if Azerbaijan is winning on the ground, if there is a peace deal that can be made that will save the lives of people – civilian and military alike – that it is worth considering. One should never forget that victory in this region can be fickle. War may have made these states, but lasting peace can serve to sustain them.

[i] Tilly, Charles (1985). “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime”, in Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (eds.), Bringing The State Back In, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 169-187.

[ii] Offe, Claus (1991). “Capitalism by Democratic Design? Democratic Theory Facing the Triple Transition in East Central Europe”, Social Research, Vol. 58, No. 4, pp. 865-881.

[iii] There have been clashes in the line of contact between Azerbaijan and the Armenia for the control of Karabakh since the 1994 ceasefire, earnestly beginning with minor encounters in 2008. The large scale fighting between the two sides began on September 27, 2020, although Azeri residents in the area of Karabakh under Azeri control state that every year there would be small fire exchanges between the two forces and that they lived in fear of Armenian sniper attacks, especially against their livestock.

[iv] Avaliani, Dimitri (2020). “The (dis)information war around Karabakh”, JAM News, 28 October 2020, (Accessed 2 November 2020).

[v] Lorusso, Marilisa (2016). “Nagorno Karabakh: The Hate Speech Factor”, OBCT Newsletter, (Accessed 1 November 2020).

[vi] See https://www.osce.org/mg/51152 for a full list of the OSCE’s Basic Principles announced on 10 July 2009, updating previous documents (Accessed 1 November 2020).

[vii] World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=AZ-AM(Accessed 1 November 2020).

[viii] The Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) reported that by 2000 as many as 1 million Armenians, almost one quarter of the population, had left Armenia mostly to seek employment in other countries. See https://iwpr.net/global-voices/brain-drain-armenia (Accessed 1 November 2020).

[ix] Hergnyan, Seda (2019). “Armenia 2018: 23.5% Live Below Poverty Line”, (Accessed 1 November 2020).

[x] Journalist Onnik J. Krikorian who has been to Karabakh, Armenia and Azerbaijan on assignment for The Independent and as a consultant for the OSCE noted this on his Twitter feed on 26 October 2020, following up with another tweet where he stated “this was a huge mistake by a populist [Pashinian], who exploited nationalism when it suited him.”

[xi] The world total of IDPs is about 38 million, Azerbaijan estimates that it currently has close to 1 million IDPs. See UNHCR (2009), Report on “Azerbaijan: Analysis of Gaps in the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPS)” (accessed 1 November 2020).

[xii] Foy, Henry (2020). “Drones and missiles tilt war with Armenia in Azerbaijan’s favor”, Financial Times, 28 October 2020.

[xiii] The exact quote from Onnik J. Krikorian’s 19 October 2020 Twitter feed is: “Despite warnings since 2011, nothing concrete to prevent war ever materialised. Of as much concern, the ‘status quo’ had become so entrenched in Armenia that whenever I’d raise this very real danger I was told many times that ‘next time we’ll take Baku.’”

[xiv] Posted on Thomas de Waal’s Twitter account on 23 October 2020.

[xv] Bekaryan, Arpi (24 October 2020). “Opinion: We Did Not Speak, We Only Whispered”, OC Media, https://oc-media.org/opinions/opinion-we-did-not-speak-we-only-whispered/ (Accessed 2 November 2020).

[xvi] One such example is The Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy (ADA) that was founded in 2006 to train diplomats for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs along with other civil servants. It was transformed into ADA University in 2014.

References

Aliyeva, Leila (2006). “Azerbaijan’s Frustrating Elections”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 17, No 2, pp. 147-160.

Altstadt, Audrey L. (2017). Frustrated Democracy in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan. New York: Columbia University Press.

Avaliani, Dimitri (2020). “The (dis)information war around Karabakh”, JAM News, 28 October 2020.

Bekaryan, Arpi (2020). “Opinion: We Did Not Speak, We Only Whispered”, OC Media, 24 October 2020.

Broers, Laurence (2019). Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry. Edinbourgh: Edinbourgh University Press.

Cornell, Svante E. (1998). “Turkey and the Conflict in Nagorno Karabakh: A Delicate Balance”, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 34, No 1, pp. 51-72.

Cornell, Svante E. (2015). Azerbaijan Since Independence. New York: Routledge.

De Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press.

Fairbanks, Charles H., Jr. (1995). “Armed Forces and Democracy: The Postcommunist Wars”, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 6, No 4, pp. 18-34.

Fairbanks, Charles H., Jr. (2002). “Weak States and Private Armies”, in Mark R. Beissinger and Crawford Young (eds.), Beyond State Crisis: Postcolonial Africa and Post-Soviet Eurasia in Comparative Perspective. Washington DC: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 129-161.

Foy, Henry (2020). “Drones and missiles tilt war with Armenia in Azerbaijan’s favor”, Financial Times, 28 October 2020.

Goltz, Thomas (1999). Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter’s Adventures in an Oil-Rich, War-Torn, Post-Soviet Republic. New York: Routledge.

Guliyev, Farid (2009). “Chapter 9: Political Elites in Azerbaijan”, in Andreas Heinrich and Heiko Pleines (eds.), Challenges of the Caspian Resource Boom: Domestic Elites and Policy-Making. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillon, pp. 117-130.

Kambeck, Michael and Ghazaryan, Sargis (eds.), (2013). Europe’s Next Avoidable War: Nagorno Karabakh. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

King, Charles (2009). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. New York: Oxford University Press.

Laitin, David D. and Suny, Ronald Grigor (1999). “Armenia and Azerbaijan: Thinking a Way Out of Karabakh”, Middle East Policy, Vol. VII, No 1, pp. 145-176.

Libaridian, Gerard J. (2007). Modern Armenia: People, Nation, State. New York: Routledge.

Lorusso, Marilisa (2016). “Nagorno Karabakh: The Hate Speech Factor”, OBCT Newsletter,12 April 2016.

Melkonian, Markar (2008). My Brother’s Road: An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia. New York: IB Tauris.

Offe, Claus (1991). “Capitalism by Democratic Design? Democratic Theory Facing the Triple Transition in East Central Europe”, Social Research, Vol. 58, No 4, pp. 865-881.

Rasizade, Alec (2011). “Nagorno-Karabakh: An Apple of Discord Between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Part 1”, Contemporary Review, Vol. 293, No. 1701.

Schaffer, Brenda (2002). Borders and Brethren: Iran and the Challenge of Azerbaijani Identity. New York: MIT Press.

Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. New York: Columbia University Press.

Tilly, Charles (1985). “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime”, in Peter Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol (eds.), Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 169-187.

Tokluoğlu, Ceylan (2013). “Azerbaijani Elite Opinion on the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict (1991 and 2002)”, Bilig, No. 64, pp. 317-342.

UNHCR (2009). Report on Azerbaijan: Analysis of Gaps in the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs).

Itır Bağdadi

Itır Bağdadi is a Lecturer at the Izmir University of Economics, and Director of its Gender and Women’s Studies Research and Application Center. As a PhD Candidate in Political Science, she has researched the post-Soviet transition of the South Caucasus, has served as an election observer in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan for international organizations and has co-directed a NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Crisis Management in Baku. Her academic research interests include gender politics, civil society, political candidates and post-Soviet politics, especially in the South Caucasus.

To cite this work: Itır Bağdadi,”If War Makes States, What Has Karabakh Made of Azerbaijan and Armenia?”, Panorama, E-publication, 9 Kasım 2020, https://www.uikpanorama.com/blog/2020/11/09/if-war-makes-states-what-has-karabakh-made-of-azerbaijan-and-armenia/

Copyright@UIKPanorama. All on-line and print rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this work belongs to the author(s) alone, and do not imply endorsement by the IRCT, the Editorial Board or the editors of the Panorama.