Department of Economics and the Crown Center for Middle East Studies,

Brandeis University, [email protected]

Introduction

This research deals with the potential for cooperation and reducing hostilities in the Middle East. While most people think about the Arab-Israeli conflict when they hear about conflicts in the Middle East, there are also many tensions and risks of conflict between other countries in the region that have nothing to do with the Arab-Israeli conflict. In this study, I concentrate on interactions between Arabs, Turks, and Iranians (ATI). Arabs, Turks, and Iranians are the largest ethnic/linguistic groups in the Middle East, generating more than 90% of the region’s population. While the Arab world is divided into more than 20 countries that share the Arab/Islamic culture, Iran and Turkey are the sole political and national representations of the Iranians and Turks, respectively. Together, they make up 30% of the total population of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).1

When we look at the history of the MENA region, we observe that the interactions between Arabs, Turks, and Iranians have been dominated by animosity and conflict in most periods. Islam has been a common cultural force that linked these three civilizations; there has also been significant cross-linguistic influence among the Arabic, Turkish, and Persian languages. Yet each group maintains its unique cultural and linguistic identity, and the rivalry between them has resulted in intense geopolitical competition and, periodically, costly wars. The most recent episode was the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), in which many Arab countries provided financial and material support to Iraq, and both countries suffered -enormous human casualties. It also imposed a heavy economic burden on both countries, as well as the wealthy oil-exporting countries that financed Iraq’s military expenses. Iran was also involved in a proxy war with Saudi Arabia for more than four decades (until the recent 2022 rapprochement). This proxy war destabilized many smaller Middle Eastern countries, such as Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

Before the rise of Islam and the arrival of Turks from Central Asia, Iran was the dominant civilization in the region. The rise of Islam shifted the balance of power to Arabs, who defeated the Iranians and spread Islam to the east, into India and Central Asia. Then, the Arabic-speaking world came under the control of the Ottoman Empire and remained under Ottoman domination for three centuries. While some Arab leaders and intellectuals were dreaming of a united “state of Arabia” after the Ottoman defeat, Western intervention and nationalist fever of the early 20th century resulted in the creation of 20 Arab countries. Now, the Arab world oscillates between a common Arab identity on the one hand and multiple national identities on the other. On many occasions during interactions with Iran and Turkey in recent decades, Arab nationalism came to the surface as a collective response.

The Turks and Iranians have also repeatedly frustrated each other’s territorial ambitions. The eastward expansion of the Ottoman empire was challenged by the Safavid dynasty of Iran for nearly two centuries.2 The Ottoman-Safavid animosity included a sectarian dimension as the Ottomans defended the Sunni sect of Islam while the Safavids viewed themselves as defenders of the Shia sect. This sectarian hostility resulted in repeated massacres of members of the “other” sect by both sides.3 Iran and the Ottoman Empire eventually signed a peace agreement in 1823, which stabilized the eastern frontier of the Ottoman Empire. However, the geopolitical rivalry between Iran and Turkey has continued. As Western domination in the Middle East continued in the 19th century, Arabs, Turks, and Iranians were forced to engage with the West at the expense of intra-regional relations.

Despite their rivalry, the Ottoman Empire and Iran had economic and cross-cultural relations before the 19th century. The Silk Road was an active trade link that passed through both empires and promoted trade. Not only did both governments collect trade transit taxes, but their economies also benefited from the exchange of commodities. Iran, for example, supplied silk to the Ottoman textile industry in Bursa.4 Even though periodic wars disrupted trade, both sides had strong incentives to restore it after each interruption. Their trade shifted from each other toward Western powers, and as they became aware of their industrial and economic inferiority compared to Europe, their urban and cultural elites adopted Western cultural norms and lifestyles. They lost interest in each other as they fixed their gaze on the West with excitement and delight.

Relations between Turkey and the other two nations are vulnerable to sporadic tensions and setbacks. The tensions with the Arab world intensified after the Arab Uprisings (2010-2011) because Turkey interfered in the domestic political affairs of some Arab countries. The Turkish-Iranian relations have not resulted in a direct conflict, but bilateral relations have been very volatile. They frequently oscillate between good relations and geopolitical tensions as both countries compete for influence in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon.

This study addresses the following questions about engagement between Arabs, Turks, and Iranians.

- What is the current level of engagement/animosity?

- What are the costs of current levels of engagement and animosities?

- What lessons can Middle Eastern nations learn about the transition to a more cooperative equilibrium from the experiences of other regions with long histories of tension and rivalry, such as Europe and South America?

- What are the potential benefits and gains of reducing or transforming these animosities into constructive competition?

- What strategies and policies can reduce the tensions and encourage positive engagement among the governments and citizens of Arab countries, Turkey, and Iran?

The analysis will pay special attention to Europe because, after many centuries of war and predation on each other, European nations overcame their differences and created the European Union. The progress of Europeans in diplomatic and economic cooperation can offer some guidelines for the Middle East. In this report, I will look at the state of interactions among governments and the engagements among the people and non-government institutions. This will include trade, tourism, and interest in each other’s sports and cultural products.

This report is primarily directed toward the three civilizations’ scholars, policymakers, artists, professionals, and business leaders. It asks them to pause momentarily and think about the dynamics and interactions among the three communities in the Middle East. I hope the issues discussed in this essay will encourage them to think about the potential gains from reducing the tensions, increasing the cultural and economic exchanges, and improving communications among the three communities.

What is the state of engagement between the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians in the modern Middle East?

There are several ways to answer this question depending on how “engagement” is defined. Here, I identify four different types of engagement and pose a few questions about how the level of every kind of engagement can be measured.

Economic engagement: What is the volume of trade and cross-border investment between countries of a region relative to the total volume of trade and investment of the region with the entire world?

People-to-people travel and tourism: How many tourists from each region visit the other two regions each year, and what is the relative significance of this tourism volume for each ATI node?

Cultural engagement: How aware and informed are people of each node about the other two? How much coverage does the media in each ATI node provide on news and significant developments in the other nodes?

Diplomatic engagement: What is the state of bilateral diplomatic relationships between the ATI nations? How many military, economic, and diplomatic cooperation treaties exist between each ATI pair? What is the frequency of wars and proxy wars among ATI nodes?

When we look at the history of interactions and engagements among Arabs, Turks, and Iranians over a long period, three important facts stand out:

- Before the arrival of Western powers in the Middle East, Arabs, Turks, and Iranians intensely engaged with each other at the people-to-people and state-to-state levels. These interactions took place in parallel with animosities and occasional wars. We can refer to this situation as an engagement-animosity equilibrium. This equilibrium arises among a collection of countries that belong to a “culture area” but simultaneously engage in rivalry and war as they compete for resources and power. A cultural area is a geographic region (consisting of several countries) that shares some cultural norms, religious beliefs, or common ideologies.5 Europe, for example, can be defined as an area that shares a common European culture. The icons and practices of this cultural area have evolved from predominantly religious/Christian in the past to a more secular culture. Still, it has nevertheless remained a cultural area throughout this evolution. Based on this definition, the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians constitute a cultural area. At the same time, these three civilizations have remained each other’s rivals and have periodically waged war against each other.

I argue that before the mid-19th century, the ATI nations interacted in an Engagement-Animosity Equilibrium. With the advent of Western colonialism and the rising influence of Western culture, the animosities have continued, but the cross-cultural influence and cultural blending among ATI have declined. As a result, the region has transitioned into an ignorance-animosity equilibrium, in which all types of engagement among ATI diminished. At the same time, they were either forced or enticed to engage with the West.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, while the Ottoman and Safavid empires were frequently at war, they also engaged in trade and cross-border population movements, contributing to cultural blending6 and cross-cultural influences. Since external powers did not dominate them, they accepted each other as rival enemies of equal status and members of a common culture area. Their relations with one another were similar to those between European countries since the 17th century (when they reversed the expansion of the Ottoman Empire and Europe, as a region, achieved military supremacy over the rest of the world.)

- The rivalry in the past did not take the form of cultural animosity and resentment toward each other’s traditions. Islam, as the shared religion, and Arabic, the language of the Quran, served as a common bond. There were many cross-cultural exchanges. Persian literature was popular and well respected in Ottoman cultural circles and among the Ottoman elite despite repeated Ottoman wars with Iran during the 16th and 17th centuries. Even when animosity was high, there was respect for the enemy as equal. The kings and rulers fought each other for territory and domination, but artists and scientists were respected well. While sectarian (Sunni-Shia) intolerance was prevalent, scientists and artists from various ethnic groups were welcomed in the courts of Abbasid khalifs, Ottoman sultans, and Safavid shahs.

- After World War II, distrust and negative bias between the ATI countries have continued at the state-to-state level, partly because of the lack of cultural and educational engagement. The opportunities for trade and security alliances with the outside world have also reduced the incentives for ATI cooperation. Arabs, Turks, and Iranians live in the shadow of superpower domination over the region. While the domination of Europe by the US and USSR (after 1945) brought Western Europe closer to each other, the superpower domination in the Middle East pushed ATI apart. A high level of distrust among ATI has compelled many smaller Arab countries (such as the GCC block) to seek protection through security arrangements with the US (and the U.K.) Many ATI countries rely on external countries rather than intra-regional security arrangements for security and economic prosperity.

What is the current state of intra-ATI relations?

At the diplomatic level, the relations among ATI countries have been and continue to be vulnerable to interference, distrust, opportunism, and betrayal (cooperation with external powers against each other). While these conditions might exist among member nations of other regions, they are more prevalent and intense among Middle Eastern countries. Furthermore, the past occurrences of these hostile postures are also part of the historical memory of the three ATI nodes and affect their perceptions of each other. Before the 1979 revolution, Iran had moderate relations with Turkey as they were both US allies and secular Westernization development projects dominated both countries. At the same time, the Shah of Iran relied on its US-backed military superiority to ignore or occasionally bully its Arab neighbors.

The 1979 revolution resulted in a significant shift in Iran’s regional policy as the Islamic regime adopted a radical foreign policy based on exporting the Islamic revolution to the entire Middle East and hostility toward the Arab allies/clients of the US. The tensions also took a sectarian Sunni-Shia dimension, particularly in Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. Not surprisingly, there was a pushback by Arab countries and Turkey, which deteriorated their relations with Iran and eventually resulted in the Iran-Iraq war.

The secular (and periodically military) governments that ruled Turkey after World War II viewed the Arab world as a low-priority region, as their primary objective ever since the 1960s was to join the European Union. Turkey’s Middle East policy was mainly supportive to the US policy. In the late 1980s, under the leadership of Turgut Özal, Turkey tried to improve its relations with the Arab countries. Turkey’s interest in the Middle East increased after 2002 with the rise of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP). It also took an ideological direction as Erdoğan expressed support for moderate Islamic groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood in the Arab world. Since 2002, Turkey’s interference in the domestic politics of some Arab countries has intensified. These interventions and Turkey’s military operations in Syria and Iraq have led to periodic tensions with Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates.

Overall, the level of diplomatic tensions and distrust among ATI is currently higher than that of other developing regions and certainly much higher than that of the European Union, which can be perceived as a global benchmark. For example, before the 2022 rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the Saudi government openly supported hostile US policies toward the Islamic Republic of Iran. In return, the Islamic government of Iran actively interfered in the internal affairs of several Arab countries. It also adopted an independent anti-Israel and anti-American policy, which often provoked and radicalized the youth in Arab countries such as Saudi Arabia (which has adopted a more moderate policy toward the Arab-Israeli conflict). Iran’s interventionist and ideological foreign policy has resulted in an intense rivalry and multiple proxy wars with Saudi Arabia. These proxy wars have affected Yemen, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon in one period or another.

Economic Relations: Yet, at the same time, economic relations among ATI are significant, although they remain below their full potential. Iran and Arab countries have complementary economic structures with Turkey. They have oil and gas, which Turkey needs. Turkey produces many manufacturing products and agricultural commodities that Iran and Arab countries import. Consequently, parallel to occasional diplomatic tensions, economic relations among ATI have experienced ups and downs in recent decades. They also remain highly vulnerable to diplomatic relations and geopolitical factors.

In the past three decades, intra-ATI tourism has also increased, but it has been mostly one-sided. Turkey is popular with Iranian and Arab tourists, and Dubai is a popular tourist destination for Iranians, but only a small number of Turks and Arabs visit Iran. The only exception is religious (Shia) tourists from Lebanon and Iraq who visit Shia holy shrines inside Iran. In some cases, their travel expenses are subsidized by the government of Iran. The Iranian government also supports and subsidizes religious tourism of Iranians to Shia holy shrines in Iraq and Syria.

Economic relations between Iran and Arab countries are vulnerable to diplomatic tensions and external interventions. Iran developed strong economic ties with the UAE in the 1990s and early 2000s. However, these relations were adversely affected by the hostilities between Iran and the United States. The US economic sanctions against Iran forced the UAE to scale back its economic ties with Iran, and many Iranian businesses operating in Dubai were forced to move their activities to other countries, such as Turkey or Malaysia, to bypass the US sanctions.

Turkey successfully expanded its economic relations with all Arab countries after President Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in 2002. The Turkish intervention in Arab affairs after the 2011 Arab Spring and its active military involvement in Syria have had an adverse effect on its trade and investment relations with major Arab economies such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt. Turkey has generally been more pragmatic in its relations with the Arab world than the Islamic Republic of Iran. Whenever there is a setback in diplomatic and economic ties, the Turkish government tries to mend the relations after a few years. It is also noticeable that Turkey’s private sector has maintained strong relations with its Arab partners even during high diplomatic tension.7

Media and cultural exchange: Another critical dimension of intra-regional interactions is the media coverage and cultural attention of regional neighbors toward each other. Cultural activities under consideration are music, cinema, literature, and visual arts. All three countries produce large amounts of cultural products and consume large volumes of cultural products from other countries. Yet, as a legacy of their attraction to the Western culture, most of the cultural products and services imported into ATI come from the West. The amount of intra-ATI cultural exchanges is limited, as is intra-ATI news coverage. How much news about neighboring countries is covered by the domestic media in each country? How are neighboring countries’ artistic and athletic activities covered in each country’s media? The answer to both questions is less desirable and less than the level of cultural exchanges in other comparable regions. If you scan the media in any ATI country, the coverage of external news is primarily focused on Western nations. The external entertainment programs are also mainly the cultural products of Western countries (or, in some cases, India).

At the same time, the intra-ATI cultural exchanges are asymmetrical. Turkey has been more successful in exporting its movies and TV drama series to Iran and Arab countries. Iran’s TV products have not succeeded in attracting audiences in Turkey and Arab countries, though some Iranian movies that have won international awards have also received attention in the MENA region. In the world of music, some Arab singers have enjoyed recognition and popularity in Iran through the Internet and satellite TV, even though they are banned in the official media of the Islamic Republic. Yet, due to language barriers, cross-consumption of musical products has been more limited than television series. A noticeable cross-cultural influence in music is the reproduction of some songs in other ATI languages.8

What are the costs of current levels of engagement and animosities?

Have the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians paid a price for their unrestricted animosity toward each other? We must first describe the harmful actions that can surface among neighbors when relations are dominated by animosity and hatred to answer this question. We can divide the costs of intra-regional conflict into three categories: a) The costs of direct conflict and warfare between two neighboring countries, b) The costs of betrayal of one country that conflicts with a third party by a regional neighbor, and c) the costs of missed opportunities for regional cooperation and coordination. When we look at the historical records of intra-ATI interactions and dynamics, we can identify many examples of these three types of costs. Furthermore, they are substantial when we add up these costs since the emergence of Islam in the 7th century. Even if we focus on the more immediate historical period since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, which led to the creation of independent Arab states, they are still substantial and partly responsible for the economic and industrial underdevelopment of the region.

The costs of confrontation: The costs of intra-ATI animosity in modern times were brought to light by the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), which set a record as the longest conventional war in the twentieth century. This bloody eight-year war caused heavy human casualties on both sides in multiple battlefields on Iran and Iraq’s shared border. It also caused considerable damage to the urban and industrial infrastructure of both countries as both sides used aerial bombardment and missiles against targets deep inside each other’s territories. The attitude of external powers toward Iran and Iraq led to its continuation as the US adopted a policy of dual containment, and all advanced countries saw the conflict as an opportunity for weapon exports to both sides. The GCC countries provided significant amounts of financial support to Iraq for weapon imports. Still, the dual containment strategy of the US and European countries denied either side a military victory for several years until a ceasefire was finally achieved in 1988.

The region remains vulnerable to similar full-scale wars among the three players. The proxy wars between Iran and Saudi Arabia came close to escalation into full-scale conflicts on several occasions, even though a rapprochement was achieved in 2023. Similarly, the conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia increased the risk of confrontation between Iran and Turkey in 2022 and 2023.

The costs of intra-ATI betrayal: The animosities and jealousy among Arabs, Turks, and Iranians have frequently resulted in the betrayal of one nation in conflicts with outside powers. The historical cases include the cooperation of Safavid Iran with Western powers against the Ottoman Empire. Similarly, the Turks viewed the Arab cooperation with the British and French empires during World War I as an act of grand betrayal, which contributed to the defeat and, ultimately, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Arab countries, in turn, view more recent examples of cooperation of Iran (before the Islamic Revolution), and Turkey with Israel as a betrayal in their struggle against Israel. The Turkish government, for example, before 2010 actively engaged in military and strategic cooperation with the US and Israel.9 In many ways, Turkey was eager to serve as a junior partner in military and covert operations of the United States and other Western countries in the Middle East as long as it was rewarded for this cooperation.

Finally, in the context of its proxy war with Iran, Saudi Arabia actively lobbied the US against signing a nuclear agreement with Iran before 2015 (when the agreement was finally signed). The Saudis also offered China more significant amounts of crude oil in return for China’s cooperation with the oil sanctions against Iran. These acts of intra-ATI betrayal impose substantial costs on the betrayed country by influencing critical geopolitical events in the region. They also perpetuate distrust and negative sentiments in the historical memory of each nation, which eventually leads to acts of revenge in the future.

Missed regional cooperation and coordination opportunities: In the competitive modern global economy, nations try to improve their international competitiveness through regional economic cooperation. The monetary integration of Europe is the best example of how regional collaboration can benefit the member states. We find similar examples of successful regional cooperation in Asia and Latin America. Conversely, there has been little progress toward regional cooperation in the Middle East region. The lack of trust and goodwill among Arabs, Turks, and Iranians has prevented successful collaboration at the regional level. However, there has been some progress among Arab sub-regions such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).

Intra-ATI animosity has also prevented the development of regional transportation infrastructure such as cross-country highways and railroads. Iran and Arab countries can benefit from the development of railroads connecting Central Asia to Iraq and the GCC region going through Iran. Yet the ongoing tensions between the GCC countries and Iran have prevented the development of a regional railroad and highway system. This failure has resulted in a significant loss of regional trade and cooperation opportunities.

The low levels of economic integration and cross-border transportation infrastructure in the MENA region have many opportunity costs and result in low costs of future intra-ATI conflicts. When neighboring countries increase their economic interdependence, they are more hesitant to adopt confrontational and opportunistic foreign policies toward each other. In some regions with a long history of intra-regional war and conflict, such as Europe, economic integration was deliberately promoted to reduce the risks and incentives for future conflicts. In the Middle East, the opposite is the case. Iran and Saudi Arabia have very low levels of bilateral trade and investment. As a result, they have no economic incentives to prevent or contain the proxy war that has dominated their bilateral relations.

What can ATI learn from the historical experience of Europe?

Tension, conflict of interest, and war among neighbors have been a typical pattern in most regions of the world, with varying degrees, throughout history. While the Middle East has experienced the largest number of wars and conflicts since World War II, Europe experienced more intra-regional conflicts than most other regions for several centuries before World War II. After 1945, a handful of nations in Western Europe initiated the process of economic cooperation. Within a short period, many other countries joined and created the modern-day European Union. The ability of Western European nations to achieve remarkable peace and cooperation after World War II and their successful integration of many Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union offer some valuable lessons for the ATI. This analysis will focus primarily on the interactions of three leading European powers: France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

Before 1945, the frequency of inter-state warfare in Europe was larger than any other region in the World. Since 1495, there have been 125 major wars between European countries. France participated in 40 of these wars. Before the 1871 German Unification, various German states participated in 30 wars against other European states between 1495 and 1871. After unification, the German Empire fought two costly World Wars10. Finally, ever since the establishment of the United Kingdom in 1707, Great Britain has been involved in at least 30 wars against at least one European state.11 Territorial competition among European powers inside the region and competition for colonial positions in other regions contributed to the high frequency of warfare among European countries. Yet, after experiencing the devastating destruction of two World Wars in the first half of the 20th century, the Europeans overcame their deep animosities and developed close ties.

World War II divided Europe into eastern and western blocs. While Eastern European nations remained under the iron fist of the former Soviet Union, a combination of internal incentives and external forces brought the countries of Western Europe together (under the US security umbrella). Surrounded by two superpowers, the US and the USSR, after 1945, and when World War II had severely damaged most European economies, the Western European countries realized that cooperation was the only way they could remain relevant and competitive in world affairs as a continent. The cooperation among Western European nations received support from the US, which also (re)-imposed democratic political institutions on the defeated nations such as Germany and Italy. As a result, all Western European countries adopted similar parliamentary democracies, which paved the way for regional cooperation.

Europe has enjoyed a remarkable and unprecedented level of peace and cooperation after World War II. European states have managed to create the European Union through a gradual process of economic integration. In parallel, they have succeeded in promoting a pan-European cultural identity (as a complement to each state’s national identity) among a large segment of each member nation’s citizens.12 The French, Germans, and British still feel competitive toward each other and maintain their national identities. Nevertheless, they have managed to channel those nationalist emotions away from war, bloodshed, and opportunistic betrayals toward one another. Instead, they have successfully edged these competitive emotions into the athletic, cultural, scientific, and technological competition.

Before World War II, when historical grievances and cultural hatreds among these three countries were as strong as, and in some historical moments, even more potent than the negative perceptions among the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians. The British had very negative and demeaning attitudes toward the Germans when the United Kingdom was more advanced than Germany in the early 19th century. The British traveler John Russell, who visited Germany several times in this era, made negative comments about the character of the Germans in his travel book:13

“..The Hanoverians (if a passing visitor is entitled to form an opinion) are of the most soberminded, plodding, easily contented people. Like all their brethren of the north of Germany, without possessing less kindness of heart, they have much less joviality, less of the good fellow, than the Austrians, and are not so genial and extravagant, even in their amusements, as the Bavarian or Wirtem…” (Russel, Page 394)

In the late 19th century, the British developed a more positive perception of Germany as they took notice of its Kultur and bureaucratic efficiency. However, this admiration was often accompanied by suspicion as the German/Prussian military grew stronger and threatened the British Empire. The initial positive perception gradually gave way to fear and distrust. These negative perceptions intensified in the early 20th century, particularly during World War I.14

Similarly, the German perceptions of Great Britain have oscillated between positive and negative extremes. Initially, Germans had positive perceptions of and admiration for the British in the 18th and early 19th centuries. They saw England as a role model of cultural enlightenment and industrial progress. These perceptions turned negative in the late 19th and early 20th century as the British Kingdom [in alliance with other powers] engaged in multiple wars to contain the rise of Germany.15

The animosity and hatred among European nations intensified in the first half of the 20th century, resulting in two World Wars. After World War II, however, the European democracies took significant steps toward economic and diplomatic cooperation in the 1950s and 1960s. Over time, they have achieved high levels of economic integration and avoided internal conflicts except peripheral conflicts such as the wars that followed the disintegration of former Yugoslavia in the 1990s and the most recent war in Ukraine.

If Europeans have been able to overcome these animosities and transform these deep-rooted hatreds into productive competition within the cooperative structure of the European Union, and if they have been able to inspire a European identity in the hearts of so many millions of people in the member states, then perhaps their success can serve as a lesson for the ATI.

People-to-People connections among Europeans: A model for ATI connectivity?

As was mentioned earlier, there are several subcultures in every country. The most common lifestyle subcultures in ATI are a) religious/traditional and b) secular/liberal lifestyles. Similarly, in the domain of political economy, you find a right (capitalist) and left (labor) divide. When we look at the contemporary relations between France and England, we observe that people connect based on their shared sub-cultures. For example, there is coordination and cooperation between the environmental movements in France and the UK (and other European countries). The conservative advocates of free enterprise cooperate to influence economic policy in both countries. In other words, interdependence among European countries is reinforced by democratic institutions that allow individuals and organizations with common goals to cooperate across EU member states and support each other freely. An even stronger bonding factor is the cross-border investments of European multinational corporations, which have created strong economic integration.

Unfortunately, for two reasons, the connectivity between people-to-people and institution-to-institution is minimal and underdeveloped among the ATI. First, weak and unfriendly diplomatic relations prevent accessible communication and travel among ATI countries, which is possible among European states. Diplomatic tensions and mutual suspicion among governments also reduce the capacities of NGOs to cooperate with their counterparts in other ATI nations. Second, even though NGOs in the MENA region show a strong desire for international cooperation, the prevailing orientation toward the West has minimized the interest of these NGOs to engage with each other. Instead, they all prefer engagement with their American and European (and, more recently, Asian) counterparts. The non-government organizations in ATI states often have stronger bonds with their Western counterparts than similar NGOs in other ATI states. For example, the environmental NGOs in Turkey are more interested in connecting with environmental groups in Europe and gaining recognition among Western nations than cooperating with Arab and Iranian environmental movements. The same applies to the environmental movement in the Arab world and Iran. We observe a similar lack of connection among political organizations that share a common ideology (perhaps with the exception of the Muslim Brotherhood- the Arab MB leaders enjoy some support in Turkey and have been hosted by the AKP government.) Similarly, the labor movements or the labor rights activists in Iran and Turkey have little interaction or exchange of ideas- unlike the robust cross-border connectivity of pro-labor parties and labor movement organizations in the European Union.

The only exception to this pervasive mutual neglect in recent years are the Islamic and humanitarian NGOs based in Turkey. With the encouragement and support of the AKP government, these NGOs made some progress in opening chapters and conducting humanitarian activities in several Arab countries16. Even the activities of these NGOs, however, suffered a setback after the Arab Spring because of the deterioration of Turkey’s diplomatic relations with the Arab World over its support of the Muslim Brotherhood organizations.

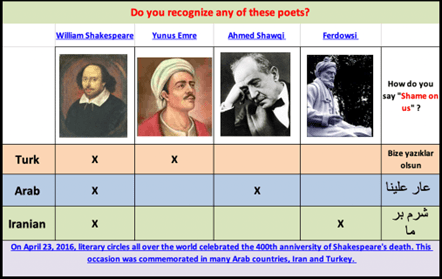

Art, Culture, and Literature: Europe can serve as a role model for these types of social and cultural connectivity for ATI. In the educational system of most European countries, the coverage of the shared European culture and literature is substantial. Overall, the most valuable lesson that the deep cooperation among Europeans can offer to Arabs, Turks, and Iranians is that it is possible for a region that was overwhelmed by deep and historical animosities in the past to transform itself and achieve a high level of harmony and cooperation. There is also an extreme cross-country interest in arts and literature among European countries. This pan-European cultural interest is much older than the recent political and economic integration after World War II. In literature and philosophy, the linkages are centuries old and reflect the shared influence of the classic pre-Christianity Greek culture and the Enlightenment. Its roots in music go back to the late 18th century, which William Weber described as the “rise of mass culture in European musical life.”17 Several classical musicians such as Beethoven, Bach, and Mozart have enjoyed universal popularity in all European countries ever since, regardless of their national identity, and this popularity has transcended multiple periods of war and rivalries in the continent. The same applies to icons of literature and visual arts such as Charles Dickens, Honore de Balzac, Claude Monet, and Leonardo da Vinci. In contrast, the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians remain highly ignorant of each other’s art and literature. How many Turks and Arabs are familiar with the Iranian painter Kkamal-ol-Molk? How many Turks and Iranians are familiar with prominent Arab Artists such as Ibn Arabi and Khalil Gibran? How many Iranians and Arabs are familiar with prominent Turkish Ottoman artists such as Osman Hamdi Bey or Abdulcelil Levni? Unfortunately, the answer to these three questions is: “only very few.”

There is very little mutual interest among these national cultures across the Middle Eastern countries. Even though some citizens are not influenced by feelings of admiration for the West, the negative perceptions and lack of interest among ATI are so strong that the three ATI cultures do not connect based on their shared cultural norms and icons. As another example, the three ATI cultures have rich literary histories in prose and poetry, but they remain ignorant of each other’s literary icons. Neither the educational system, nor the cultural elite of ATI nations, promotes mutual admiration for each other’s literature and culture. This mutual ignorance in the field of literature is demonstrated in Figure 1.

It is worth mentioning three factors that have contributed to Europe’s ‘cooperation success.’ First, despite continuous warfare and tension among European states, there has been a long history of marriage among the monarchies and royal families.18 These dynastic marriages not only contributed to occasional diplomatic alliances but also facilitated cultural exchanges among European nations.19 There is some evidence that the expansion of marriage networks among European royal families contributed to a reduction in the frequency of inter-European wars.20 The second factor is the common educational experience of Europe’s political elite, who created the early vision of the European Community. Many of these pioneers and founders had studied in the US in the 1950s and 1960s and shared an awareness of how the federal government functioned in the US. This shared vision contributed to their success in political innovations that shaped the relations between the collective European institutions and the national governments. Since many academic, business and political elite in MENA countries have received their university education in Europe and North America, they are familiar with the federal government system in the US and the high level of economic and political integration in Europe. Perhaps this shared vision can play a similarly positive role in developing regional institutions for ATI. Third, European countries have created mechanisms to promote student mobility and exchange at the university level. While several programs toward this goal have been introduced since the 1980s, the most popular and successful one is the ERASMUS program (European Community Action Scheme for the Mobility of University Students). Currently, there is no comparable student mobility program among ATI countries. While many students from each Middle Eastern country study abroad -the popular destinations are North America and Europe- only a very small number of Middle Eastern students study in other Middle Eastern countries. The most popular ATI countries for these students are Turkey and the UAE. The universities can also serve as centers for the mobility of faculty and research scholars. The GCC universities have progressed in this direction by liberalizing their higher education system. In addition to the international universities, which enjoy high diversity among their faculty, the national universities are also relatively diverse. A large number of Iranian and Turkish instructors teach at the GCC universities. However, the university with the highest international staff ratio in the Middle East region is Al Akhawayn University of Ifrane (Morocco), in which more than 60% of the faculty and staff are either non-Moroccans or binational citizens.21

While advocates of ATI cooperation will envy what the European nations have achieved, some of the unique conditions that contributed to the European Union project are unavailable in the Middle East. First, the United States served as a geopolitical big brother that actively promoted Western Europe’s economic and political integration after World War II. Neither the US nor any other global power has played a similar role in the Middle East.22 Second, when the European nations initiated the EU integration process, their political systems were similar (liberal democracies), and they faced a common external adversary, the former Soviet Union. Both factors played a positive role in the creation of the EU.

The political systems of ATI countries are more diverse and are vulnerable to sudden revolutionary change with the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran and the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt. The advocates of ATI cooperation have to adapt to the existing political systems in the region and find pragmatic strategies to win support from the political leadership of each country in accordance with its own political institutions and power structure. Similarly, the region lacks any shared perception of a common external threat that can bring the ATI nations closer together. On the contrary, Turkey, Iran, and major Arab countries are locked in a rivalry and geopolitical competition, which has forced some of them to seek external allies and protectors. It is possible, however, that as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict continues, a shared sympathy for Palestinians might result in some political and cultural cooperation among the ATI. After the October 7 Israel war on GAZA, there have been several collective and bilateral meetings between Iran, Turkey, and Arab countries on this crisis. However, this joint opposition to Israel is a weaker force for cooperation among ATI relative to the perceived threat of the Soviet Union among Western European countries after World War II. Despite all these differences, Europe can still offer many lessons to advocates of ATI cooperation.

Lessons from the Experiences of South America

Unlike the Middle East and Europe, South America is a young continent where the current nations gained independence from European colonial powers beginning in the early 19th century. The strong influence of Spanish and Portuguese cultures has contributed to many cultural similarities among the South American countries. It has also served as one of the factors that has led to the low frequency of war and conflict among South American countries in the past two centuries. These cultural similarities and ease of communication have promoted a culture of mediation and conflict resolution23 in the region.

The region’s low frequency of interstate wars has been labeled “The Long Peace in South America.”24 Unlike the Middle East, which has suffered more wars and conflicts than any other region in the 20th century, South America has only had one major war since 1900: the Chaco war (1932-1935) between Paraguay and Bolivia. According to the Correlates of War data set,25 while the global community experienced 227 wars between 1816 and 2007, only eight occurred in South America. Yet, at the same time, many South American countries have experienced frequent episodes of intrastate and domestic conflicts. Some scholars have argued that preoccupation with domestic political and ethnic conflicts has reduced the tendency of South American countries for interstate wars.26

This benign regional neighborhood environment has paved the way for economic cooperation, and the achievements are impressive compared to other developing and emerging regions of the world. However, they fall short of what has been achieved in the European Union. The South American nations initiated several regional economic cooperation agreements since the 1950s. While the progress was initially slow, they transitioned from authoritarian and military rule to democracy in the 1980s and 1990s. The intra-regional economic relations are supported by several regional trade and investment agreements, such as The Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR), which is committed to the promotion of democracy and economic development.27 South America’s long peace experience does not offer any lesson on how to overcome extreme animosity and transition into cooperation, but it sheds light on the potential benefits of peaceful coexistence and positive cross-border perceptions. In addition to gains from economic cooperation, these nations have benefited from a substantial peace dividend.28 When we compare the military expenditures (as a percent of GDP) in various regions of the world, we observe that the eleven South American countries have a lower military expenditure ratio than any other region.29 In 2002, South America’s share of global military expenditures was only 2.1% compared to 8.2% in the Middle East.30 They have also achieved significant progress in the removal of restrictions on travel and trade.

While South America and the Middle East have lived in the shadow of external powers (predominantly the US), the impact of superpower intervention varies in these two regions. The influence of the US on foreign policy priorities of Latin American nations has discouraged them from focusing on disputes with their neighbors due to its emphasis on containing the Soviet Union’s influence in the region31. This has not been the case in the Middle East, where rivalries between the US and other external powers have resulted in more divisions and conflicts. Furthermore, South America’s civilian and military ruling elite have not seen any advantage in going to war against their neighbors because of the potential domestic risks of failed military campaigns.32

Lessons from the Experiences of South Asia: World Bank’s #OneSouthAsia Initiative

Another region with potential lessons for the Middle East on regional cooperation is South Asia, which has been ripe with inter-state tensions and conflicts. The region remains vulnerable to the deep-rooted animosity between India and Pakistan and many smaller-scale conflicts involving other South Asian countries. Not surprisingly, the level of cooperation and regional integration in South Asia is shallow compared to Europe and South America. India, Pakistan, and six other South Asian countries created the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1987, focusing on economic cooperation. However, the lack of trust and ongoing tensions between India and Pakistan have prevented SAARC from making substantial progress.33

In a more recent development, the region has received external support for promoting cooperation and connectivity. The World Bank launched the Regional Integration, Cooperation, and Engagement Program for South Asia (#OneSouthAsia) in 2020.34 The initiative is also primarily focused on promoting economic cooperation and increasing the volume of trade and investment among South Asian countries. With financial support from the World Bank and several Western countries, this initiative has promoted the creation of several cross-border transportation corridors, electricity trade, and educational programs for mutual assistance in the face of regional disasters. Another significant contribution of this program is that it has facilitated regional dialogue on a wide variety of development issues, such as the potential for regional cooperation among higher education institutions and enhancing the role of women in cross-border trade and commerce.

Perhaps the lesson ATI can learn from #OneSouthAsia is that a benevolent external stakeholder might play a positive and influential role in promoting dialogue and cooperation among ATI countries at both the governmental and people-to-people levels. Organizing conferences and dialogues on common issues of regional concern can help reduce distrust and pave the way for participation in regional projects such as the World Bank’s #OneAsia initiative. The World Bank itself, however, might not be able to serve an influential role in the Middle East region because of the ongoing US and international sanctions on Iran and some other countries. These sanctions might limit the World Bank’s ability to work with Iranian government organizations.

In recent years, China has emerged as the leading trade partner of all Middle Eastern countries and enjoys good diplomatic relations. As a result, China might be positioned to serve as the external promoter of regional cooperation. Indeed, China has already demonstrated its effectiveness in mediating between rival Middle Eastern countries. In 2023, China played an important mediation role in the rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia35. China is incentivized to promote peace and cooperation among MENA countries because of its economic and strategic interests. Since 2005, China has become highly dependent on the import of oil and natural gas from the Middle East. Tension and instability among its MENA oil suppliers can harm China’s economy by disrupting oil imports. Furthermore, the Middle East is an important region for China’s global trade and connectivity plan called the Belt and Road Initiative. Several important highways and railroads that connect China to Europe go through Iran and Turkey. China is also promoting the extension of this transportation network into Iraq, Syria, and the GCC countries.

It is also worth noting that the lack of progress in SAARC due to poor cooperation between India and Pakistan has promoted a sub-regional cooperation initiative in South Asia with the participation of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, and Nepal. These countries created the BBIN Initiative36 in 2001, and one of their more ambitious projects is the 2015 BBIN Motor Vehicle Agreement (BBIN-MVA), which will ease cross-border ground transport for passenger and cargo vehicles. There might also be a lesson in this experiment for ATI.

Overall, the most important lesson that the advocates of regional cooperation in the Middle East can learn from these regionalist initiatives in South Asia is that even when there is deep tension and animosity among some neighbors in a region, there are steps that can be taken toward regional cooperation. Even when cooperation among all neighbors is adversely affected by animosity between two members (as has been the case between India and Pakistan in South Asia), subregional cooperation on some issues is possible. Furthermore, the experience of South Asia shows that if progress in regional cooperation on one policy proves difficult, it is possible to make progress in cooperation on other policies. There is no need for a unanimous agreement on a comprehensive agreement like that of the European Union.

ATI Transition toward Engagement and Productive Competition? Practical First Steps and Challenges

In light of the above discussions about the underlying historical and cultural factors that affect how Arabs, Turks, and Iranians interact with each other, there are several practical steps that the advocates of ATI cooperation can take. The analysis in this section assumes that there is at least a small group of citizens in Iran, Turkey, and at least some Arab countries that are interested in promoting regional cooperation and friendship. In discussing the strategies and practical steps toward ATI cooperation, it is important to be realistic about what can be achieved and which goals are beyond reach in the near future. While a high level of regional integration similar to the European Union might be desirable, it is beyond reach.

Europeans have reached a level of regional affinity and mutual acceptance years ahead of the Middle East. The present conditions in Europe can be described as ‘warm peace’37, in which not only are the nations at peace and using force to settle disputes out of the question, but they also a high level of economic and cultural engagement. At this stage, the ATI must first transition from the regional ‘cold/proxy war’ conditions to ‘cold peace’ and then gradually move toward a warm peace.

The danger associated with prolonged cold/proxy wars is that they carry a high risk of escalation into full-scale wars and conflicts, like the Iran-Iraq war. During the 2017 Qatar crisis, Turkey came close to confronting the Saudi-UAE duo. Iran’s proxy war with Saudi Arabia has always carried an escalation risk in recent years. Therefore, transitioning from the state of Cold/Proxy War (which can best describe the current state of affairs among ATI) to Cold Peace is a crucial first step. The first task at hand in this direction is to redefine the terms of hatred and estrangement among the ATI. Since there is rivalry, jealousy, and an overlapping quest for regional leadership, the three nations should be encouraged to see each other not as strangers (willing to inflict unlimited harm on each other) but as siblings. As members of the same family, siblings generally contain the damage they might inflict on each other during occasional outbursts of anger.

Arab culture has a famous proverb: Me and my ‘siblings’ against my cousin. Me and my cousins against the world. (I have slightly modified this proverb in the interest of gender equality by substituting “sibling” for “brother”!) The ideal end goal for ATI cooperation is to reach a stage of acceptance and camaraderie among the governments and people that resembles the relations among siblings in a family, particularly when managing tension, jealousy, and disputes.

Here are a few suggestions for cooperation and effective anger management among ATI neighbors:

- ATI Incubator: There is a group of people in every Middle Eastern country that look at Europe with envy and dream of peace and cooperation among Arabs, Turks, and Iranians. They need to find each other and create a multi-country civil society for ATI cooperation (which we can call ATI Incubator for convenience). The internet and social media can facilitate this process. Once a small group of ten or fifteen interested individuals find each other, they can start by creating a website and an association. As the news about this idea spreads, it will attract more supporters, and some high-income individuals who support regional cooperation might also provide financing. There is already precedence for this process. The corruption-fighting organization Transparency International is the brainchild of German entrepreneur Peter Eigen38. This NGO began as a small organization in 1993, and it now has chapters in many countries and has played an important role in fighting corruption.

- Advocating regional cooperation: Once the ATI advocates (the advocates for regional cooperation among ATI) find each other and create an association or NGO, they can launch many programs to promote their agenda. Some obvious examples include a) social media outreach, b) organizing events, and c) publishing educational/advocacy articles and videos.

- Promoting ATI cooperation under authoritarian and hybrid political systems: The promotion of European integration began in the democratic political environment of post-World War II Western Europe (partly imposed on Europeans by the US). Most governments in the Middle East are either authoritarian or semi-democratic. Promoting regional cooperation might be more challenging in an authoritarian environment, but it is not impossible. Most governments in the Middle East are authoritarian developmental states interested in elevating their country’s economic prosperity (while limiting political and human rights). The ATI advocates in each country must adopt their message and campaign strategy to the political environment to maximize their influence on the ruling political elite and the ordinary people.

The early advocates of Europe believed that promoting human rights and democratic institutions was a prerequisite for European integration. This belief strongly impacted their choice of strategies and policies toward European integration. The ATI advocates in the Middle East will face significant resistance from the political elite if they follow the same path. It is better to focus on the positive win-win consequences of ATI cooperation for the people and the existing ruling elite in the ATI countries.

- Winning hearts and minds, hoping for policy congruence: The ATI states are the leading players in any significant steps toward promoting peace and regional cooperation. The ATI advocates must focus on direct communication with the ruling elite and indirectly by influencing public opinion.

When we look at the regional policy of the political leaders in Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia, we find regionalist leaders (advocates of regional cooperation) in all three. These include Turgut Özal (1989-1993) in Turkey, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) in Iran, and King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz al-Saud (2005-2015) in Saudi Arabia.39 Congruence of three regionalist leaders in three ATI nodes can create a unique window of opportunity for genuine progress toward ATI convergence. The ATI advocacy activities can increase the likelihood of such a congruence. This type of congruence can also arise from the ashes of a catastrophic event with a significant emotional charge for all three. The October 7 Hamas attack on Israel and Israel’s response in Gaza is an example of such an event, which might bring the ATI leaders closer together.

Who Needs an ATI Initiative?

The advocates of ATI integration will likely face pushback from regionalists interested in an alliance with a different group of neighbors in their respective countries. The Arab elite might argue that ‘we have 20 Arab countries with a vast land area and a population of 450 million. Instead of focusing on regional integration with Turkey and Iran, we can work toward Arab regional integration, emphasizing Arab nationalism and a shared Arab culture’. This Pan-Arab regionalism enjoys strong support among the academic and political elite in many Arab countries, and it can reduce the appeal of ATI cooperation for some of them.

There are two strong regionalist tendencies in Turkey. The Pan-Turkic camp calls for regional cooperation with the Turkic-speaking countries of Central Asia (Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan). There is also a popular track that still dreams of Turkey’s full integration into the EU despite strong resistance from several European nations. Similarly, there is a Shia-centered regionalist tendency in Iran. The ruling Islamic regime prefers economic and diplomatic coordination with Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon (the Shia crescent).

Similarly, there has been a Pan-Iranian movement in Iran, which aspires for regional cooperation among Iran, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan (where variations of Persian are spoken). Iran’s Islamic ruling elite also has its regionalist aspirations, which focus on supporting the Shia populations throughout the Middle East. These alternative regionalist visions already have strong constituencies in the Middle East, and any attempt to present the ATI cooperation initiative as a replacement for them will likely face strong resistance. Instead, the ATI advocates should present the concept of ATI cooperation as a complement to these nationalist visions. The primary objective of ATI advocacy, which is to bring about a transition from cold/proxy war to cold peace among Arabs, Turks, and Iranians, does not contradict each ATI node’s membership in other multinational economic and geopolitical agreements.

Conclusion

The Middle East has suffered more inter-state wars and civil wars than most other regions of the world after World War II. While different regions, such as South America and South Asia, were in a similar predicament in the 1960s and 1970s, they have achieved a higher level of peace and regional cooperation over time than the Middle East. The three major civilizations of the region, Arabs, Turks, and Iranians, must be mindful of the persistent rivalries and tensions among them. These tensions have led to repeated war and destruction in the past, and they are likely to cause new conflicts. It is up to the people and governments of these nations to work toward reducing hostilities and promoting regional cooperation. Other regions, such as Europe, have successfully increased their collaboration and interdependencies after centuries of conflict. The Middle East cannot achieve peace and prosperity unless the Arabs, Turks, and Iranians find a way to manage their rivalries and move toward political and economic cooperation.

References

Baltacioglu-Brammer, A. (2016) Safavid Conversion Propaganda in Ottoman Anatolia and the Ottoman Reaction, 1440s-1630s. PhD diss., The Ohio State University.

Bauerkämper, A., & Eisenberg, C. (2006). Introduction: Perceptions of Britain in Germany. Britain as a Model of Modern Society? .

Battaglino, J. M. (2008), Palabras mortales ¿Rearme y carrera armamentista en América del Sur? Nueva Sociedad Nº 15, pp. 23-34.

Benzell, S. G., & Cooke, K. (2021). A network of thrones: Kinship and conflict in europe, 1495–1918. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13(3), 102-133.

Chakma, B. (2020). Beyond SAARC: Sub-Regional and Trans-Regional Cooperation. In South Asian Regionalism (pp. 121-136). Bristol University Press.

Cohen, J.S. and Ward, M.D. (1996), “Towards A Peace Dividend in the Middle East”, Gleditsch, N.P., Bjerkholt, O., Cappelen, A., Smith, R. and Dunne, J.P. (Ed.) The Peace Dividend (Contributions to Economic Analysis, Vol. 235), Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 425-437. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0573-8555(1996)0000235024

Franchi, T., Migon, E. X. F. G., & Villarreal, R. X. J. (2017). Taxonomy of interstate conflicts: is South America a peaceful region?. Brazilian Political Science Review, 11, e0008.

Gregg, G. S. (2005). The Middle East: a cultural psychology. Oxford University Press.

Haran, V. P. (2018). Regional Cooperation in South Asia. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 13(3), 195-208.

Kacowicz, A. M. (1998), Zones of peace in the third world New York: Suny Press.

Matthee, R. (2019) Safavid Iran and the “Turkish Question” or How to Avoid a War on Multiple Fronts. Iranian Studies 52, no. 3-4, 513-542.

Miller, B. (2015). Explaining the warm peace in Europe versus the shifts between hot war and cold peace in the Middle East. In Regional Peacemaking and Conflict Management (pp. 7-42). Routledge.

Munassar, Omar. (2021). National role conceptions and orientations of Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia as competing regional powers in the Middle East: 1979-2020. PhD diss., Bursa Uludağ University (Turkey).

Nihat, Ç. & İşeri, E. (2016). Islamically oriented humanitarian NGOs in Turkey: AKP foreign policy parallelism, Turkish Studies, 17:3, 429-448, DOI: 10.1080/14683849.2016.1204917 .

Palos, J. L., & Sánchez, M. S. (Eds.). (2017). Early Modern Dynastic Marriages and Cultural Transfer. Taylor & Francis.

Perry, J. R. (2011). Cultural currents in the Turco-Persian world of Safavid and post-Safavid times. In New Perspectives on Safavid Iran (pp. 84-96). Routledge.

Radziwill, P. C. (1915) The royal marriage market of Europe. Funk and Wagnalls Company.

Russell, J. (1825). A Tour in Germany, and Some of the Southern Provinces of the Austrian Empire: In the Years 1820, 1821, 1822. Wells & Lilly.

Sarkees, M., & Wayman, F. (2010). Resort to War, 1816-2007. (No Title).

Jash Dr, A. (2023). Saudi-Iran Deal: A Test Case of China’s Role as an International Mediator. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2023/06/23/saudi-iran-deal-a-test-case-of-chinas-role-as-an-international-mediator/ .

Soy, N. H. (2016) A comparison of Turkey and Iran’s Soft Power in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. PhD diss., Qatar University (Qatar).

Treverton, G. F. (1984). Interstate Conflict in Latin America (No. 154). Latin American Program, The Wilson Center.

Tsutomu, S. (2013). Trading Networks in Western Asia and the Iranian Silk Trade. In Commercial Networks in Modern Asia (pp. 235-250). Routledge.

Warden, R. (2022, May, 26). Mobility in MENA, Two Steps Forward, One Step Back. University World News. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20220524144433433.

Weber, W. (1994) Mass Culture and the Reshaping of European Musical Taste, 1770-1870. International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 175-190.

World Bank’s Approach to South Asia Regional Integration, Cooperation, and Engagement (SA RICE) 2020-2023: Main Report (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/116411598021247454/Main-Report.

Appendix:

A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the intra-ATI Attitudes

There are several similarities in the attitudes and perceptions of Arabs, Turks, and Iranians toward each other. These similarities are rooted in their shared historical experiences, the most important of which are consistent military, economic, and territorial setbacks in encounters with the European powers, including Russia. These defeats, in combination with the exposure of these societies to the dynamic and vibrant internal cultures of leading Western countries such as the UK and, more recently, the United States, have led to a polarized cultural response in ATI societies. It has resulted in the emergence of a pro-Western sub-culture and an anti-Western sub-culture simultaneously.

A-1) Admiration for the Western Culture and Inferiority Complex: One segment of the predominantly urban and educated citizens in each ATI society displays a strong attraction and admiration toward Western culture, lifestyle, norms, and social values, and these tendencies have persisted since they first emerged in the mid-19th century. This attraction is evident in the imitation of Western culture (dress style, music, TV programs, etc.), the strong desire of ATI citizens to travel and reside in these countries, and a strong preference for studying in their educational institutions.

Two tendencies of the pro-Western sub-culture in ATI societies are worth noticing. First, the intense focus and gaze toward the West have reduced the interest of ATI citizens in each other. Western countries remain the most popular travel destinations for citizens of ATI countries. The West is also the most popular destination for higher education, and the university graduates that return to their countries are often heavily influenced by the Western culture (of the country where they gained their university degrees.) As a result of these travel and cultural interactions, these ATI citizens are more familiar with Western cultures than each other’s. Suppose you test the knowledge of an Iranian about the history and culture of England and Saudi Arabia. The results will likely show a higher familiarity with England than Saudi Arabia or any other Middle Eastern country. Similarly, suppose you survey the travels of the cosmopolitan Turks that live in Istanbul and major cities in the western region of Turkey. You are likely to find a similar result. Their foreign travels are likely limited to European countries and rarely any visits to Middle Eastern countries (with the occasional exception of Dubai).

Second, this segment of ATI citizens often perceive their society and culture as being inferior to the West. As an extension of this feeling of inferiority, they also perceive other Middle Eastern countries through the same lens. In other words, a Westernized Egyptian might view the Egyptian, Iranian, and Turkish societies as inferior to Western countries. As a result, they often treat Western citizens with more respect than the citizens of other ATI countries. If, for example, two tourists visit Turkey, one from Germany and one from Morocco, the German tourist will receive more attention and respect from an average Turk. In contrast, the Moroccan tourist might face neglect and indifference. This perception is partially the result of ATI societies’ lack of interest and lack of knowledge about each other. This lack of knowledge is, to a large extent, a result of the limited coverage of neighboring countries in the media and educational curriculum of these countries.

There is some evidence that society passes these attitudes to children at an early age. A recent study in Iran by Yazdi et al. (2020) has found that when Iranian children ages 6 to 12 (in a middle-class neighborhood near Tehran) participated in a survey of attitudes toward Arab, American, and Iranian children of their age groups, they expressed a more positive attitude toward Americans relative to Arabs.40 These differences reflect the attitudes of the adults (parents and relatives) who express their opinions about various nationalities in front of the children in family settings. They also reflect the ineffectiveness of the negative images that formal educational textbooks in Iran have tried to convey about the US after the 1979 revolution.

The intra-ATI negative perceptions are also reinforced by historical hangovers that are rooted in centuries of rivalries and wars among ATI. For example, the swift defeat of the Sassanid Empire by the early Islamic armies in the 7th century is perceived as the most significant historical humiliation by many Iranians. Neither the invasion of Alexander (which destroyed the Persepolis) nor the Mongolian invasion have evoked so much anger in the historical memory of Iranians as the defeat of the Sassanid Empire. Furthermore, some secular and well-educated Iranians allow the memory of this defeat to affect their perceptions of contemporary Arabs.

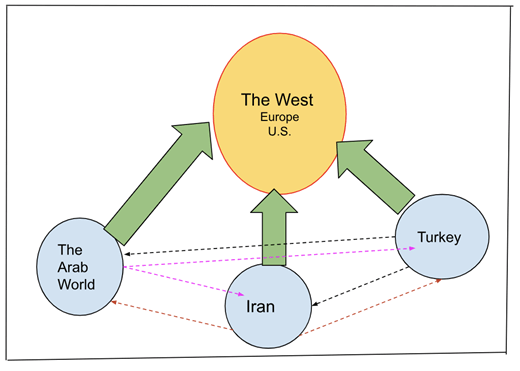

The West-centric attitudes of ATI people are demonstrated in Figure 1. In this symbolic image, the thickness of an arrow represents the level of attention and interest of the citizens of a country toward another country. The educated and urban classes in Iran, Turkey, and the Arab world show strong interest in the West, as demonstrated by the thick green arrows but weak cultural bonds with each other (the narrow-dashed arrows).

A-2) The Apathetic/Anti-Western Subculture in ATI Societies: There is also a sizable group in every ATI society that harbors negative attitudes toward the West. This subculture is influenced not only by the historical memory of their country’s decline versus the West but also by some current policies of the US (and to a lesser extent Europe) toward the region, which is best demonstrated by the Western support for Israel in the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict. Some of these individuals also resent the popularity of Western lifestyles and cultural values in their society. They advocate for the preservation of the conservative and traditional culture, which is more compatible with Islamic norms. In Middle Eastern societies, most people in this anti-western subculture belong to the middle and lower socioeconomic classes. At the same time, it includes only a tiny segment of upper-class individuals- mostly businesspersons in the traditional merchant sector.

While this subculture is likely to be less interested in Western countries and, potentially, more interested in other ATI countries, it also suffers from a lack of knowledge and awareness about the current conditions of the ATI neighbors. In addition, both subcultures are influenced by memories of rivalries and wars with ATI neighbors. As a result, the absence of attraction toward the West in the second subculture has not translated into a desire for more cooperation and more affinity toward the ATI neighbors. Furthermore, while the social base of the anti-Western subculture might be relatively large, the limited resources and lower level of education of most of its members have limited its capacity to engage in cross-border cultural exchanges through travel or trade.

A-3) National Greatness and “I am Second” Self-Perception: The citizens of ATI countries not only compare their country with the advanced nations but with other ATI countries. In this attempt to rank their country, they often put advanced countries like the US or Germany at a higher rank than their own. When determining the relative rank of their country relative to other ATI countries, each node tends to see its position as higher than the other two. In other words, they adopt an “I am second” posture. For example, if you ask a Turkish citizen to rank the US, Turkey, Iran, and the Arab world, s/he is likely to rank the US at the highest, followed by Turkey, Iran, or the Arab World. If you ask an Iranian the same question, the answer is likely to be: The US, Iran, Turkey, Arab world. If you ask an Arab, their answer is expected to be “the US, Arab World, Turkey, Iran”, or “The US, Arab world, Iran, Turkey”. In other words, each node tends to view itself at a higher status than the other two, which means that while I acknowledge that my culture/civilization ranks lower than the West, I consider it superior to my ATI neighbors.

This “I am second” mindset is also partly a result of ignorance of each ATI node about the achievements of its ATI neighbors. The result of this mindset is that it can lead to misunderstanding and frustration in interactions among ATI citizens. Based on this perception of superiority, the citizens of an ATI node might feel that they have not been treated with the amount of respect and attention that they deserve, which might lead to misunderstanding and tension. At the state-to-state level, the conflicting perceptions of relative status can lead to intense competition for regional leadership, as explained in the next section.

A-4) Competing Narratives of Regional Leadership: As an extension of the “I am second” mindset, the ruling elite of Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia all have claims of regional leadership in their geopolitical narrative. These self-defined leadership roles serve as justifications for regional intervention and are multi-dimensional. Iran’s Islamic regime has aspired to create a Shia crescent (Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon), lead the axis of resistance against Israel, and be recognized as the leader of revolutionary and anti-imperialist Islam. Turkey is interested in leading and promoting the liberal brand of Islam in the Middle East and the Muslim Brotherhood. The Erdoğan government also views itself as the defender of the Sunni countries against Iran’s ambitions. Saudi Arabia believes that it is the leader of the Muslim world (because of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina), the leader of the Arab world (because of its oil wealth and economic domination), and the defender of the Arab world against interventions by Iran and Turkey. In terms of regional ambitions, Iran and Turkey view themselves as entitled to intervene in Arab countries, but Saudi Arabia is only interested in defending the Arab world against these neighbors. It has not shown any interest in interfering in the domestic affairs of Iran and Turkey except in a reactionary and responsive posture to their interventions in the Arab world. These competing claims to leadership have contributed to several episodes of bilateral tensions in the region. They have often resulted in zero-sum competitions for power and influence.

Nader Habibi, Prof. Dr., Brandeis University’s Crown Center for Middle East Studies

Nader Habibi is the Henry J. Leir Professor of Practice in the Economics of the Middle East at Brandeis University’s Crown Center for Middle East Studies. Before joining Brandeis University in June 2007, he served as managing director of economic forecasting and risk analysis for Middle East and North Africa in Global Insight Ltd. Mr. Habibi has worked in academic and research institutions in Iran, Turkey and the United States since 1987. He earned his PhD in Economics from Michigan State University. His most recent research projects are: a) Economic relations of Middle Eastern countries with China, b) analysis of the excess supply of college graduates in Middle Eastern countries, c) impact of economic sanctions on Iranian economy. Habibi also served as director of Islamic and Middle East Studies at Brandeis University (August 2014-August 2019). He has published a work of fiction about Middle East geopolitics titled: Three Stories One Middle East (2014). Links to his publications are available at https://naderhabibi.blogspot.com/.

To cite this work: Nader Habibi, “Arabs, Turks, Iranians: Prospects for Cooperation and Prevention of Conflict”, Panorama, Online, 27 June 2024, https://www.uikpanorama.com/blog/2024/06/27/nh-coop-conflict/

Copyright@UIKPanorama.All on-line and print rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this work belongs to the author(s) alone, and do not imply endorsement by the IRCT, the Editorial Board or the editors of the Panorama.